by Terry Conway

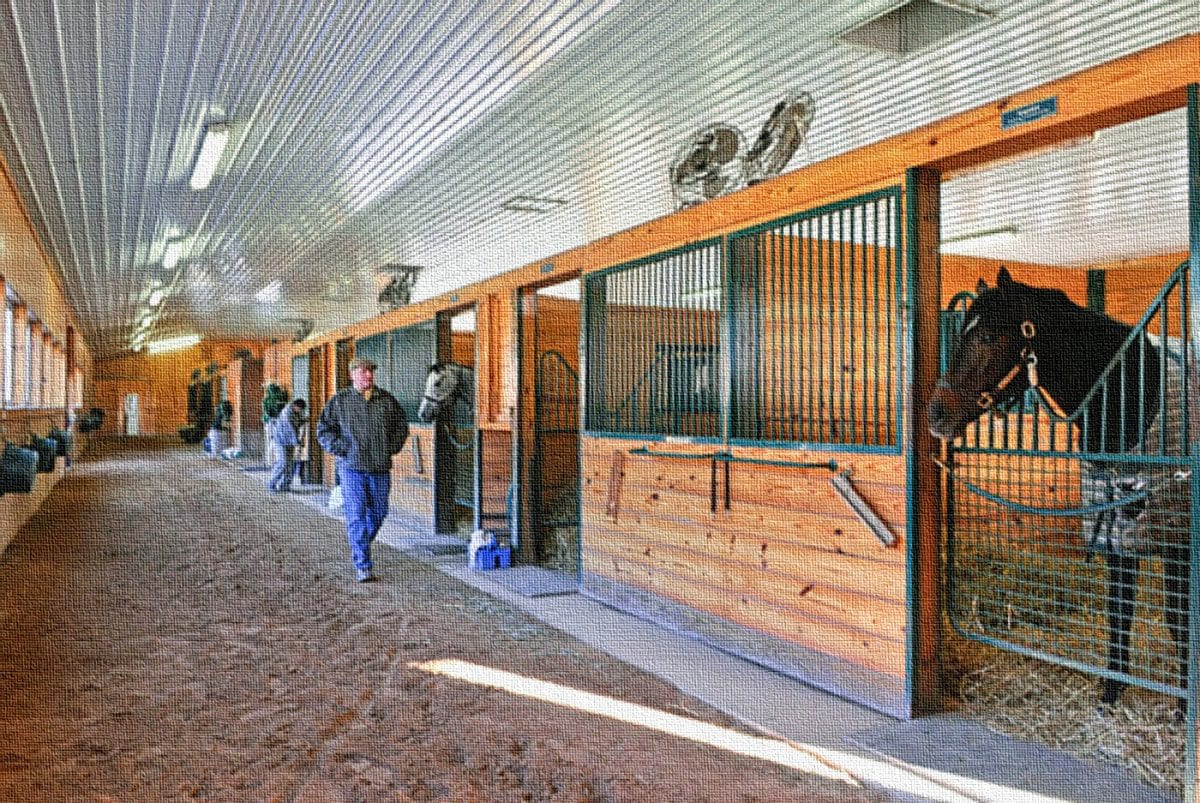

Last October on an overcast, rainy morning Paynter finally became a racehorse again. After months of shuttling from one equine hospital to another, the handsome bay colt stepped off a shipping van and walked into a stall in Bruce Jackson’s barn. The colt checked out his thoroughbred neighbors then began to inhale a mound of hay in a corner of the stall.

If you looked up “incredible trooper” in a dictionary, surely you would find a picture of Paynter. Two days after his 2012 Haskell Invitational victory, he first showed signs of illness. Over the next two months he waged near-death battles with colitis, laminitis, and finally a surgery to remove a 35 centimeter area of abscessed tissue from his cecum, a pouch in the horse’s large intestine. Last summer and fall, his weight fell from 1,100 pounds to the low 900 pound range.

The odds were incredibly stacked against him but Paynter beat them time and again. His stay at the Fair Hill Equine Therapy Center was a huge step on the road to recovery.

“Our mission was to let him put on some weight, relax and just be a horse,” recalled the therapy center’s owner Jackson in a lounge adjacent to his office. “He just needed to get back to familiar surroundings, get his strength back and put all that time at equine hospitals behind him. We put him on a special diet to help him gain back weight. Our goal was to make him a happy horse.”

For the first few weeks there was no significant walking, just a short trip from his stall to go outside several times a day to graze as much as he wanted. Mike Call, a longtime Fair Hill horseman, was his grazing buddy.

“Paynter was still really sick when he came here, but he showed so much patience. He knew we were trying to help him,” Call remembered. “He came in wearing these safety boots, but after awhile we took them off and just let him walk over the cold grass. His feet got better and better.”

A big concern was the colitis and colic. Call and other barn staff would take the horse’s temperature three to four times a day and note it on a chart next to the stall door. It would spike, but Paynter always bounced back. His appetite was good, and he kept putting on weight. By late December the colt had gained more than 100 pounds, and owner Ahmad Zayat flew him back to his home base, Bob Baffert’s Santa Anita barn.

“He kept getting stronger and stronger to where I had two hands on the shank,” Call recalled with a half-smile. “He’s an alpha male. You could see in his eyes that competitive fire he exhibited as a three-year old. We all really hoped he would make it back to the races.”

They got their wish in mid-June when the impeccably-bred Paynter — by uber-sire Awesome Again out of the Tiznow mare Tizso — returned with an emphatic victory in a seven-furlong allowance race at Hollywood Park. Leading throughout, he pulled away from seven overmatched rivals to win by five lengths in a speedy 1:21.86.

“Everyone gathered in Bruce’s office to watch,” Call said. “When he opened it up down the stretch we all went crazy. I think that gives us the greatest satisfaction, when our patients come back and do well.”

Two wide on both turns Paynter was beaten just a half-length in the Grade-2 San Diego at Del Mar on July 27. His next likely start is in the Woodward Stakes on the dirt at Saratoga on Aug. 31. Another possibility is the $1 million Pacific Classic on the all-weather track at Del Mar on Aug. 25.

[pullquote]“When [Paynter] opened it up down the stretch we all went crazy,” said Mike Call. “I think that gives us the greatest satisfaction, when our patients come back and do well.”[/pullquote]The Fair Hill Training Center, which opened in 1983, has had its share of top-flight thoroughbreds over the past decade including Derby winners Barbaro, Animal Kingdom and Orb (here), Belmont winner Union Rags, Breeders’ Cup Turf winner Better Talk Now and a string of multiple stakes winners. In recent years Jackson’s therapy center has become a smart choice for horses from owners and trainers not normally stabled at Fair Hill’s 18 barns.

Owner Dave Wilkenfeld sent 2-year old Vyjack to Fair Hill in 2012 for some early lessons. Before that stay the colt didn’t exactly cooperate with his handlers. He grew so unruly he wouldn’t go to the track and had to be gelded. Vyjack returned last spring and was treated for a lung infection, undergoing regular treatments in the hyperbaric chamber.

Mucho Macho Man, runner up in 2012 Breeders’ Cup, was shipped to Fair Hill last February to be treated for a mild virus and a subsequent bacterial infection with visits to the hyperbaric chamber. For much of the spring he trained on the dirt or Tapeta tracks and got time in a turnout paddock.

“We considered coming to Fair Hill last year, it’s a great facility,” said Mucho Macho Man’s trainer Kathy Ritvo. “It gives you a lot of options. The horses that are there look great.”

Bruce Jackson, left, escorts a horse out of the hyperbaric chamber. Photo by Fair Hill Equine Therapy Center.

The therapy center’s 30 employees are in constant motion, guiding horses from their stall to various treatments, including the hyperbaric chamber. A relatively new therapy in the equine world over the past decade, the chamber design and treatment protocol draws directly from the foundation of the therapy in human medicine. Oxygen therapy has long been a life-saving remedy for ocean divers suffering from the bends and victims of smoke inhalation.

On my recent visit to Jackson’s facility a four-year old colt, recuperating from knee surgery to remove bone chips, is led into a two-inch thick steel chamber and the door closes. There is a hissing sound– air being pumped into the unit. Off to the side, a technician sits at a control panel adjusting several dials while monitoring a video screen that shows the dark bay colt standing quietly inside.

The chamber is a spacious, stall-like area with padded walls and rubber mats on the floor where the animal is free to roam around or lie down. The colt steps over to the chamber’s porthole window and peers out intently at a couple of visitors during the painless procedure.

Inside the chamber, pressure slowly builds, forcing 100 percent pure oxygen (regular air has 21 percent) into the room where it is absorbed by the animal through both the skin and lungs.

Horses suffering from serious conditions might undergo anywhere from two to 30 treatments, depending on the condition. The increased amount of usable dissolved oxygen available to the horse helps to reduce inflammation, including redness, swelling, heat, and pain. It provides injured and diseased tissues with the oxygen necessary to begin and continue the healing process. It is also thought to deliver and increase the effectiveness of antibiotics being used to treat the affected area.

“It really helps horses get over a hard race, or three hard races, a hard campaign or even a hard workout,” Jackson noted. “It delivers the oxygen to the body in much higher concentrations than would occur normally. That’s what I call ‘cell fuel.’ It’s what helps them heal, replicate and repair.

“Let’s say you played basketball or some other sport and you overdid it and were kind of stiff and sore. All those micro-tears from over-exertion are what the chamber will heal.”

Orb’s trainer Shug McGaughey says he’s in the early stages of learning about this treatment.

“Bruce has been guiding me through all how this all works,” said McGaughey who has shipped eight horses to Jackson’s therapy center this summer. “The main thing I take away is it helps horses recover muscle-wise and respiratory-wise.”

[pullquote]“These therapies enhance the horse’s recovery,” Jackson said, “but it doesn’t make the horse run any faster.”[/pullquote]The cost of the machine and the adjunct building was roughly $500,000. Three technicians operate the chamber and attend to 10 to 12 horses a day, and it is open seven days a week. Since the chamber was installed in June 2008 they’ve treated more than 8,200 horses— roughly 80 percent racehorses with a growing clientele of top-level dressage and event horses.

Each treatment lasts 45 minutes with 15 minutes on either side to prepare the horse and to decompress from the machine. The cost per session is $300. Many veterinarians believe oxygen therapy is the biggest breakthrough in equine treatment since the use of ultrasound back in the 1980s.

Jackson whips out his I-Pad to show me pictures of a hunter who suffered a severe laceration to his front leg last January. The leg was a gory mess. You could see the cannon bone. The horse began oxygen therapy treatments. Jackson flips to pictures from week one to week seven. The ongoing healing process of the leg was remarkable.

Jackson’s also got a vibration stall ($30 a session) that is designed to increase blood flow through the horse. It also promotes hoof growth. The horse stands on a frequency-controlled vibration plate. It was developed by a Scandinavian standardbred trainer,

It may look futuristic, but to Bruce Jackson and his staff, it’s today’s technology. Photo by Fair Hill Equine Therapy Center.

“They relax and enjoy the movement and stand quietly during the process,” Jackson said. “The vibration plate is great for their feet and sore backs, reduces muscle soreness and inflammation. Many horses at Fair Hill utilize it as a warm-up before heading off to the track for training in the morning.”

Every horse matters at Jackson’s therapy center.

“It’s been great getting recognition by treating high-profile horse like Paynter and Orb, but it’s equally rewarding working with other horses that have issues, so they can come back stronger, more able to compete,” Jackson said.

Equine medical therapy is often a composite of multiple medical treatments used to promote healing and recovery.

“These therapies enhance the horse’s recovery,” Jackson said, “but it doesn’t make the horse run any faster.”