by George Rowand

Don’t expect lightning to strike twice.

That’s the second lesson I learned breeding horses.

In the first part of this series, I told about our plan to buy yearling fillies, race them and then turn them into broodmares. That initial plan was a complete failure; none of the three fillies we bought ever won a race, and two of them didn’t even get to the track.

Still, we went ahead with the second part of the plan, turned them into broodmares, and started breeding them to cheap stallions. At this, we were successful, but by no means do I consider myself a breeding “expert.” I have some ideas that I gathered from breeding good and bad horses, and from talking to everyone I could think of about the art and science of breeding.

The first lesson I learned, which I recounted last time, was to know your mare.

The small breeder trying to breed stakes-winning horses must first understand that the odds are severely stacked against us. The average stallion produces about 3 percent stakes winners from foals, which means that 97 out of 100 are not stakes winners.

That’s true for everyone, of course, but the scale of the big breeding farms moves the odds in their favor. I once was on a breeding farm in Kentucky, and the farm manager said, “We had 279 yearlings last year.” I thought, “We had one yearling last year, and if he’s any good, he will have to run against the best of your 279!”

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’]http://www.theracingbiz.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/georgerowand.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]George Rowand started Bonner Farm in Virginia with his family in 1980. From a mare that won just $450, and using modest stallions, he bred and managed two Grade 1 winners and two other graded stakes winners. He is the author of “Diary of a Dream: My Journey in Thoroughbred Racing.”[/author_info] [/author]

Yet, that the odds are against one makes the challenge that much greater, and the reward that much more fulfilling. And year after year, we see small breeders produce top-class horses.

For us, the key to the success we enjoyed was our mare, Highland Mills. When we got her and two other fillies — all of whom washed out as racehorses — I made it my mission to find out everything I could about them. I talked with their breeders. I found their half-siblings and talked to those owners. I talk with the stud managers of their sires. It gave me a better picture of what I had when I started breeding them, far more than just looking at the pedigree page.

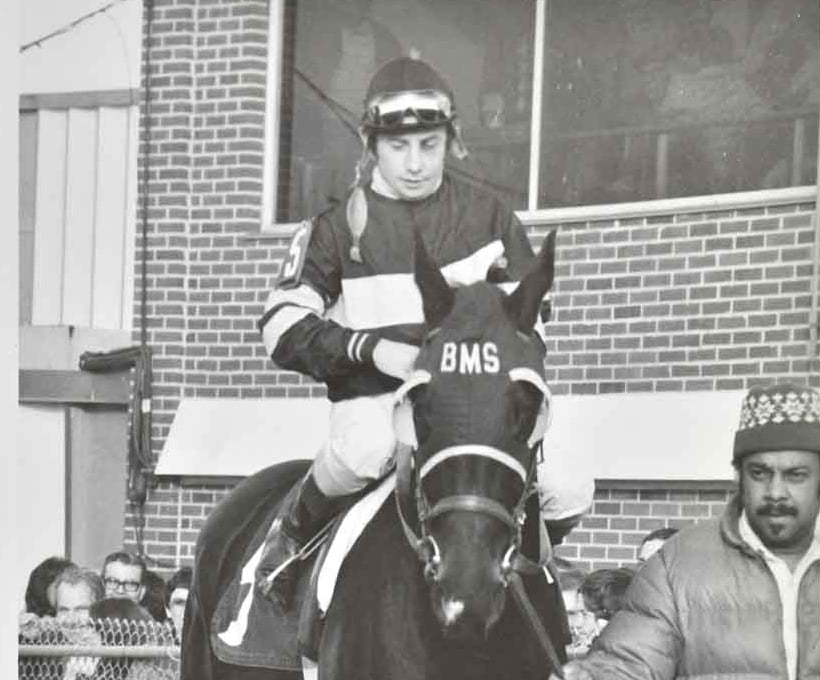

The first horse of Highland Mills that we kept was Highland Springs (here), who was by Lucy’s Axe, a stallion that stood for $3,500. I loved the mating, and he lived up to his pedigree by getting better with age. From humble beginnings in maiden claiming company, he ended up being a multiple graded-stakes winner of over $400,000, a Saratoga track-record setter, and a Breeders’ Cup runner.

As it turned out, Highland Mills was just getting started.

Her next foal was by Faraway Son, who stood for $5,000. This gelding had more talent than Highland Springs – everybody at every barn he ever was in said that – but he was injured a couple of times and didn’t live up to his potential. Still, he was stakes-placed.

Her third foal was a filly by Nasty And Bold, a stallion with a $6,500 stud fee. She was Miss Josh, who started her racing career by losing a $50,000 maiden claimer, a $25,000 maiden claimer, and an $18,500 maiden claimer. She broke her maiden in a $12,000 maiden claimer on the dirt, and then really blossomed on the grass. She won $758,000, the Grade 1 Gamely Handicap, and seven other stakes races.

She was an Eclipse Award finalist for Champion Turf Mare.

[pullquote]Highland Mills produced four graded-stakes winners by four different stallions and four different bloodlines. Breeding to different stallions was intentional.[/pullquote]

Two years later, Highland Mills produced Highland Crystal by Raise A Man, who stood for $5,000. She won $380,000 and was a graded-stakes winner. We sold her as a broodmare prospect, and her second foal brought $1.35 million as a yearling.

One year later, Highland Mills produced Royal Mountain Inn, a son of Vigors, who stood for $10,500. He was a large, fragile individual, but he set a stakes record in the grade 1 Man o’ War Stakes and was unbeaten at Belmont Park. He had world-class talent.

Highland Mills later produced another stakes-placed runner, making six stakes horses in her first eight foals.

As a racehorse, Highland Mills was a complete failure, and the strength of her pedigree was not apparent on the surface. There was quality there, but we had to find it, and then we had to try to emphasize her strengths while trying to overcome her weaknesses. I want to highlight that word: “try.”

[pullquote]I’ve never said that we knew what we were doing when we bred those horses. We knew what we were trying to do, and there is a difference.[/pullquote]

I’ve never said that we knew what we were doing when we bred those horses. We knew what we were trying to do, and there is a difference. If you look at a five-cross pedigree of just about any horse, you can pretty quickly spot if the breeders along the way knew what they were trying to do.

Highland Mills produced four graded-stakes winners by four different stallions and four different bloodlines. Breeding to different stallions was intentional.

After the first couple of stakes winners came along, horse people asked me why I didn’t go back to the same stallions that had produced them.

The answer was simple, and, for me, it’s point number two in breeding good horses.

If lightning struck once in one spot, why would you think it would strike twice?

Look at the statistics. Good stallions produce stakes winners once in ten tries. The stallions I was dealing with were producing fewer than that. By getting a stakes winner by a certain stallion, I had beaten the odds once. I just never believed that I could do it twice. How many full-siblings are both successful stakes winners? Yes, there are a handful, but my guess would be that the mare in question would have had stakes winners by other stallions as well.

Maybe my attitude would have been different if I had been interested in selling the foal, but because we were racing, I just never believed that it was a wise use of our resources to try to get lucky twice.