With breeding season upon us, The Racing Biz continues a state-by-state review of the incentive programs and status of the industry in each mid-Atlantic jurisdiction. Up today, Pennsylvania.

by Linda Dougherty

Pennsylvania’s breeding program became one of the most lucrative in the country after the bill to authorize slot machines was signed into law by Governor Ed Rendell on July 4, 2004, and it still is.

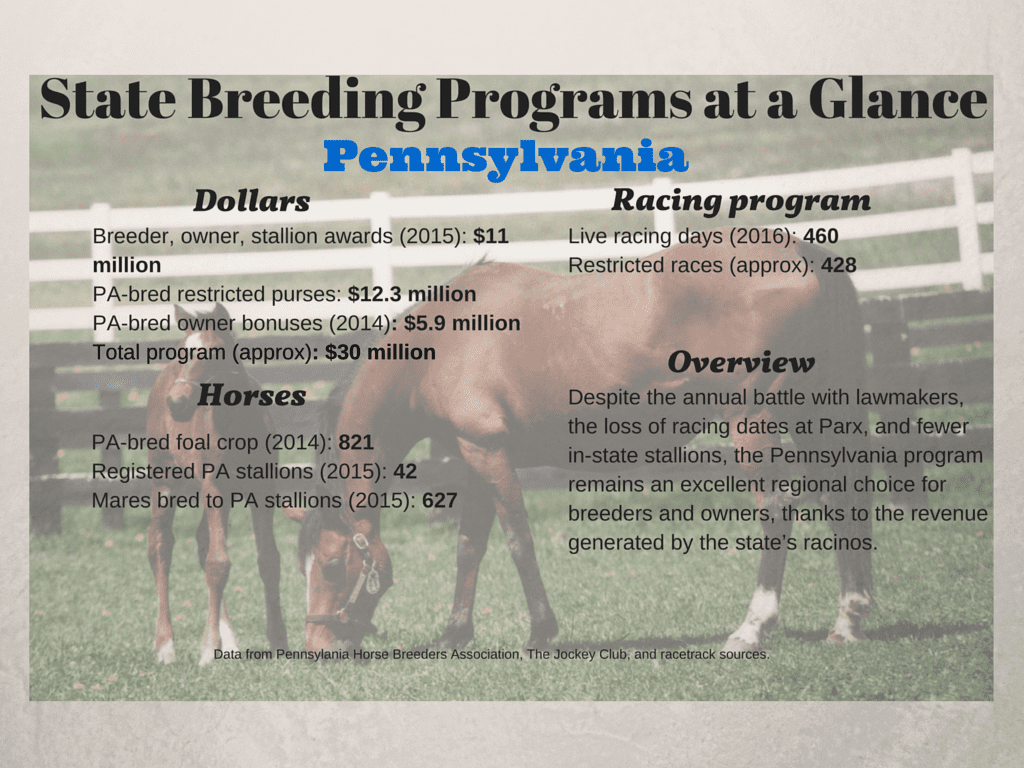

Thanks to a steady stream of slots revenue, the state’s breeding fund more than doubled in just one year – from $7.2 million in 2006 to $15.7 million in 2007 – and it has continued to grow. From 2011 through 2015, the Pennsylvania breeding fund gave out more than $143 million in owner, breeder and stallion awards as well as owner bonuses, reaching its peak in 2014, when $33,035,700 was dispersed, making it far and away the richest of any program in the mid-Atlantic region.

With that amount of money available, owners and breeders were drawn to Pennsylvania from across the country, including leading breeders Ken and Sarah Ramsey. Stallions arrived from other states, and new farms sprang up practically overnight, like Penn Ridge Farms in Harrisburg, Ghost Ridge Farms in York, Dana Point Farm in Lenhartsville, and Northview-Pa in Peach Bottom.

But despite the richness of the program, the foal crop has been in a steady decline, from its peak of 1,540 foals in 2009 to 821 foals in 2014, the most recent year available from The Jockey Club. The number of mares bred to Pennsylvania stallions also peaked in 2009, with 1,753 mares bred to 128 stallions, and then dropped by more than half in 2015, with 627 mares bred to 42 stallions, also according to The Jockey Club.

The reasons are varied, but perhaps the main one is that the breeding fund has been under siege every year by Pennsylvania lawmakers, beginning with the Rendell administration and continuing through the Corbett and Wolf administrations. The reduction of dates at Parx Racing this year, from more than 200 to fewer than 160, due in large part to shrinking pari-mutuel revenue, has also been concerning. Many breeders, especially those who do not own farms in the state, have chosen to foal their mares where they feel the breeding program is more secure.

Brian Sanfratello, the executive director of the Pennsylvania Horse Breeders Association, said there is a “perception” among some breeders that the breeding fund could be pilfered at will by Harrisburg lawmakers. But he points out that the Pennsylvania program has remained stable since 2007 and is likely to remain stable in the future; it has provided more than $20 million to participants in each of the last four years.

Robert C. Roffey, a Florida-based breeder who foaled mares for several years in Pennsylvania despite the fact that he owns a farm in Ocala, stopped breeding in Pennsylvania for just that reason.

“I’m inclined to think that I’m going to stay in Florida going forward, as the political situation in Pennsylvania is worrisome,” he said.

One person who has seen the decline first-hand is Dr. William Solomon, owner of Pin Oak Lane Farm in New Freedom. Solomon said that he foaled upwards of 150 mares in 2009, at the height of the Pennsylvania program’s explosive growth, but that the number will drop to 40 this year.

“You don’t buy shares in a company if you know the company’s going down,” he said.

Solomon blames the lack of a robust restricted program with sire stakes, like New York offers, for the program’s sagging popularity. As an example, in 2014, 823 races were run at New York racetracks exclusively for New York-breds, with purses totaling $44.5 million. Last year, 428 restricted races were carded at Pennsylvania’s three racetracks, with total restricted purses of $12.3 million and a restricted stakes schedule of 22 races worth $1.82 million.

“There’s a lot of money available in owner and breeder awards, but you have to finish one-two-three,” said Solomon. “With fewer race days and bigger purses, you’re competing against ship-ins. Unless we get a restricted program like New York’s, the numbers will continue to drop.”

While Solomon’s Pin Oak Lane remains a stalwart among Pennsylvania’s breeding establishments, several new farms that sprouted in the wake of slots legislation have either gone out of business or are for sale, often as a result of owners not realizing how much money it costs to run a big equine operation.

Two of the most prominent examples are Ghost Ridge Farms, which arrived on the scene with a bang in 2008 when they assembled a stallion roster featuring the popular Smarty Jones and top young sire Jump Start, but got out of the stallion business in 2011, barely three years later. Penn Ridge Farms, built outside of Harrisburg, stood dual classic winner Real Quiet and several other stallions before disbanding its stallion division and being put on the market.

Still, despite the annual battle with lawmakers, the loss of racing dates at Parx, and fewer in-state stallions, the Pennsylvania program remains an excellent regional choice for breeders and owners, thanks to the revenue generated by the state’s racinos.

(Featured photo, of Untapable racing at Parx, by Bill Denver / EQUI-PHOTO.)