Horse books for the holidays: Missionville book review

by Frank Vespe

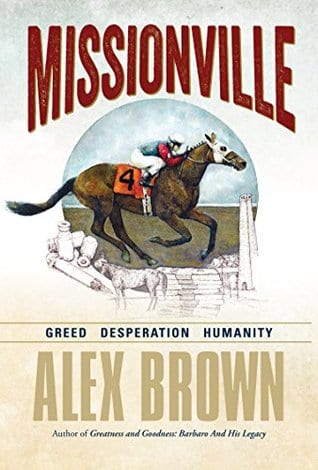

The cover of Missionville, the novel by former exercise rider– and author of Greatness and Goodness: Barbaro and his legacy — Alex Brown, tells the tale. There’s the racehorse and the pile of cash, the syringe and the empty vials. And for good measure, there’s the subtitle: Greed. Desperation. Humanity.

Missionville is, not unlike its main characters, on a mission: to reveal what Brown portrays as the seamy underbelly of Thoroughbred racing in the United States, specifically what he suggests is a sort of “claim-to-table” pipeline, in which horses drop down the claiming ranks until they’re siphoned off into kill pens, whence to Quebec slaughterhouses and off to European dinner tables.

Missionville tells the tale of Pete, a no-account horse trainer given to rather sudden epiphanies, and Amanda, a beautiful banker with an unacknowledged drinking problem who dabbles in rescuing horses from the kill pens.

Pete plies his trade at the Missionville racetrack, a lower-level, mostly claiming track in rural Pennsylvania (and if that makes you think Penn National, well, it’s perhaps no surprise that Brown galloped horses there). He has a small string, three or four runners at any one time, and a too-demanding but otherwise off-screen owner.

For a variety of reasons, Pete finds himself, for a few hundred bucks, reduced to driving a shipment of horses, including some Thoroughbreds, to slaughter – a decision that spurs him into a multi-day drinking binge, leads to an epiphany that he needs to find a new line of work, and imperils his nascent relationship with Amanda.

But then Pete, Amanda, and Amanda’s friend Sarah hatch a plan to figure out – and reveal – whose horses are ending up in the slaughter pens and who’s responsible for getting them there. Along the way, the trio adds an elderly but still intrepid newspaper reporter and uncovers a bevy of other none-too-savory activity – including a jockey using a battery to shock horses, a vet treating runners with frog juice, and a track owner whose money doesn’t come from his on-the-level business. Oh, and the clockers are involved in falsifying workout times, though at whose direction, and for whose benefit, isn’t entirely clear.

Missionville isn’t a mystery, really; the only possible bad guys turn out to be the bad guys, just as Pete and Amanda surmised. And it’s not really a thriller; there aren’t many twists or turns, and plans generally go as envisioned.

Missionville isn’t a mystery, really; the only possible bad guys turn out to be the bad guys, just as Pete and Amanda surmised. And it’s not really a thriller; there aren’t many twists or turns, and plans generally go as envisioned.

The characters are fairly bland – Pete and Amanda take turns telling the tale, but they both have essentially the same voice – and though the story trips along at a solid pace, it’s neither character nor plot that’s driving the action.

Indeed, at some level Missionville is less a novel than a bill of indictment. But against whom?

It’s not really against the story’s bad guys. In fact, the reader never meets the only truly bad guys in the story.

You could say the slaughter industry, and you’d certainly be right that that is one party. Brown writes strongly of Pete’s emotional struggle as he moonlights driving horses to slaughter, of looking into the horses’ eyes and knowing that he’ll be the one to usher them to their demise. And Sarah, whose horse was claimed by one of the story’s main bad guys and then found his way into the slaughter pipeline, agonizes over his expected fate.

But Brown is aiming at more than just an indictment of the slaughter industry. In fact, the story is full of people who end up connected to that realm not because they’re bad guys but via circumstance.

In an industry with plenty of money at the top, those at the bottom are in a constant battle to stay one step ahead of the bill collector, and to avoid falling afoul of those less scrupulous. There’s Pete, with his ill-fated foray into driving horses to slaughter; Jake, who finds himself the main conduit from racetrack to slaughterhouse; and others who, willfully or otherwise, turn a blind eye to what is not that hard to see.

Indeed, Brown’s true target here is the racing industry itself. In that regard, the story’s climax actually comes about halfway through. When Hank Fredericks, a longtime local trainer fallen on hard times, commits suicide, Pete is (somewhat mysteriously) enlisted to say a few words at his memorial service.

“I believe Hank took his life because Missionville had sucked that life right out of him,” he tells the crowd.

The book’s epigraph is, “This is a work of fiction. The truth would be unbelievable.”

But a better choice might well have been, “The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is that good men do nothing.”

Because in the end, it is the willingness of many to turn a blind eye that degrades the industry in Missionville and lets the bad guys have a long run of success. The same, Brown suggests, holds true of racing around the country.