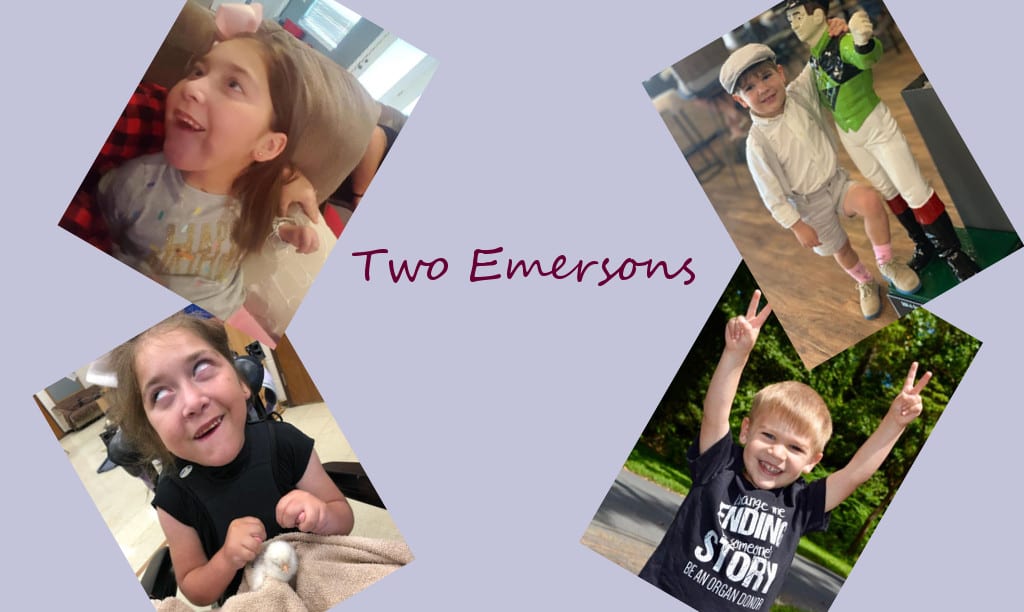

Two Emersons, strong and brave

Trainer Phil Schoenthal’s son Emerson shakes hands with jockey Victor Rosales after Gifted Heart won her second race. Photo by Dottie Miller.

Last fall, trainer Phil Schoenthal and his wife Sarah found themselves in an unendurable position. Their three-year-old son Emerson was living in the hospital, suffering from the effects of a rare heart condition, and in need of a new heart.

Their fears and concerns about their own son were more than any parent should bear. Their suffering was redoubled because they knew that in order for their son to live, another child had to die.

“It was terrible,” said Schoenthal, the emotion in his voice belying the inadequacy of the description. “We knew that some family was going to experience a horrible tragedy, and that was hard for us to deal with it. We asked people to pray for that family, whoever it was, in addition to us.”

It had been a whirlwind. In June, Emerson had been having some minor health issues that his father characterized as “no big deal, kids’ stuff.”

The Schoenthals were surprised that the doctor recommended an echocardiogram — a sonogram of the heart — but nonetheless scheduled one, assuming that would be a wasted afternoon.

“Within a few hours,” he said, “our lives were changed.”

Emerson was diagnosed with an incurable heart condition called restrictive cardiomyopathy, caused by a genetic defect. Restrictive cardiomyopathy is a form of cardiomyopathy in which the walls of the heart are rigid, which prevents the heart from stretching and filling with blood properly.

At first, life continued pretty much normally, but gradually, Emerson’s heart condition began to affect his other organs. He needed to be fed through a tube, because not enough blood was flowing to his stomach for his food to be digested.

“The challenge was to keep the rest of his body healthy as he waited for a heart transplant,” Schoenthal explained.

That challenge was exacerbated just before Thanksgiving, when Emerson began to suffer from secondary organ failure. He and Sarah moved into the Johns Hopkins Children’s Center in Baltimore, less than an hour from Schoenthal’s base at Laurel Park.

Photos of Emerson Dean, left, provided by Barbara Dean. Photos of Emerson Schoenthal provided by Phil Schoenthal.

And always, on his mind was what would need to happen to another child in order for his to survive.

“I thought about it constantly,” he said, choking up nearly nine months later.

Emerson came home in February, a month after his successful transplant. His family was overjoyed, but they continued to think about the family who made Emerson’s life possible, hoping, said Schoenthal, that “they would be able to find peace and comfort in their grief.”

The Schoenthals knew nothing about the family: where they came from, what caused the child’s death, how old the donor was. Third-party services offer to connect donor and recipient families, and in the spring, the Schoenthals decided to write a letter to the family.

“There was this nameless, faceless hero out there, and I wanted to be able to put a name to him or her,” Schoenthal said.

But…what to say? How to say it?

Schoenthal agonized. He drafted. He revised, mindful of a dreadful scenario he had learned about while Emerson was in the hospital. He knew that his letter might not ever reach the recipient, because it’s not unusual in the case of child organ transplants for the donor to have died as a result of child abuse.

“If a child ends up in the hospital because of child abuse,” he said, “the child immediately becomes a ward of the state, and they become an organ donor by default.”

He paused, choked up, before continuing.

“It was really hard to deal with,” he said. “I didn’t want to feel like we got our miracle because some kid ran into the wrong asshole. I just really wanted to know that our donor was somebody who was part of a family, who was loved even though their life was short.”

About a month later, the Schoenthals heard back from the intermediary.

“They told us that the father had broken down in tears when he found out our son’s name is Emerson,” Schoenthal said. “His daughter, our donor, was named Emerson as well.”

“When I heard that,” said Barbara Dean, Emerson’s mother, “I knew I had to talk to them. It was like it was a sign.”

The Deans, who live in Louisiana, knew almost nothing about where Emerson’s heart had gone. After the surgery, they had been told that a little boy had received it, and that a six-year-old girl had received one kidney and Emerson’s liver. A 40-year-old man received Emerson’s other kidney.

Gifted Heart won at first asking at Laurel Park. Photo by Jim McCue, Maryland Jockey Club.

Then they received the Schoenthals’ letter, which also included a picture of their son. The two couples became Facebook friends and learned each other’s stories.

“It was very emotional,” said Dean. “I was excited to hear that he was doing so well, and super excited that my daughter had been able to help someone else live, but bittersweet, because of that, she’s not here.”

When Emerson Dean was 18 months old, she suffered a non-fatal drowning that left her physically and neurologically impaired. She was confined to a wheelchair and ate through a feeding tube, neither of which affected her joie de vivre and love of music.

“’Frozen’ and ‘Tangled’ were her favorites,” said her mother, at times choking up. “She was sweet and amazing and she lived a wonderfully full life.”

On Wednesday, January 16 of this year, Dean took video of her daughter, singing and laughing and playing. When Dean went to wake Emerson—called Emmy—for school the next day, she didn’t respond. Dean started CPR and emergency services were able to get Emmy to the local hospital, where the doctors told the family that it was “nothing short of a miracle that she has a heartbeat.”

Emmy was transferred to Children’s Hospital New Orleans, where she went on life support. Her organs began to fail, and her family made the excruciating decision to remove their daughter from the machines keeping her alive.

Shortly after Emerson Schoenthal’s diagnosis, Phil had begun recording video updates to post on YouTube, the visual version of a CaringBridge or illness blog. He recorded an emotional one on the day of the transplant on January 18.

“I was overcome with grief, for that nameless family who child was giving us her heart,” he said.

Throughout the eight months of his son’s illness, Schoenthal still had a stable to run. His clients stuck with him, and the Maryland racing community offered support and stability in a time of uncertainty.

Several of his owners wanted to name horses in honor of what the Schoenthal family went through; so far, about a half-dozen horses have names that allude to Emerson, and the trainer intends to adds names that invoke the importance of organ donation.

Gifted Heart, a two-year-old Maryland-bred filly, ran off the screen in her début in early June, winning by nine lengths. Owned by Rashid’s Thoroughbred Racing, Linda Walls, Rick Wallace, and Schoenthal’s Kingdom Bloodstock, she ran her record to two-for-two with a win at Laurel Park July 27.

“When Gifted Heart won,” said Schoenthal, “I felt all those emotions again. I hadn’t been emotional in a long time because Emerson was home and doing well, but when I was walking to the winner’s circle, I just lost it. I was standing there crying.”

Another two-year-old Maryland-bred, as yet unraced, is named for both children: Emerson means “strong and brave,” and that’s what the chestnut gelding is called.

“I really hope that horse can win,” said Schoenthal.

The Dean and Schoenthal families stay in occasional touch; they have no plans to meet. Separated by a thousand miles, they are connected through Facebook, and through the beating heart that kept two Emersons alive.

“My wife recorded the sound of our son’s heartbeat,” said Schoenthal, “and we made a Build-A-Bear. We dressed the bear in a little butterfly tutu and sent it to the Deans.”

“Not much kept Emmy down,” said her mother. “If you had a bad day, you just had to talk to her. Her laugh was contagious, and it’s one of the main things I miss about her.

“Everybody knew her, everybody loved her,” she went on, through tears. “It’s a definitely a loss for the whole community.”

At the end of Sonnet 18, the “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day” sonnet, Shakespeare noted of the poem that he had just written about the beauty of a friend, “So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.”

Four hundred years later, those words may well have been written about the heart of a little girl, giving life to a little boy. Two Emersons, strong and brave indeed.