GENERAL GEORGE, FRITCHIE, AND NAMES NOT CHOSEN

A minor brouhaha emerged on Twitter earlier this week when word began to spread that Laurel Park’s General George Stakes (G3) had been re-christened the General’s Stakes, with some observers claiming that the Maryland Jockey Club was trying to erase George Washington, the race’s namesake according to the MJC media guide, which also claims that Washington visited MJC races in 1762, 1771, 1772, and 1773. Cancel culture run amok, some posited.

Turns out that the death of the General George had been greatly exaggerated.

The controversy was attributed to an “internal miscommunication,” according to a Stronach Group spokesperson, and not the next step in the Stronach Group’s quest to become the wokest racing entity out there.

Not everyone is buying the “internal miscommunication” line, but the General George has retained its rightful place on the Laurel calendar and will be contested this Saturday, Feb. 13, two days before the national holiday honoring Washington, sharing a card with the Barbara Fritchie Stakes (G3).

Fans of the latter race who think that horse racing should “stick to racing” and “keep politics out of it” may be dismayed to learn about the eponym of the Fritchie.

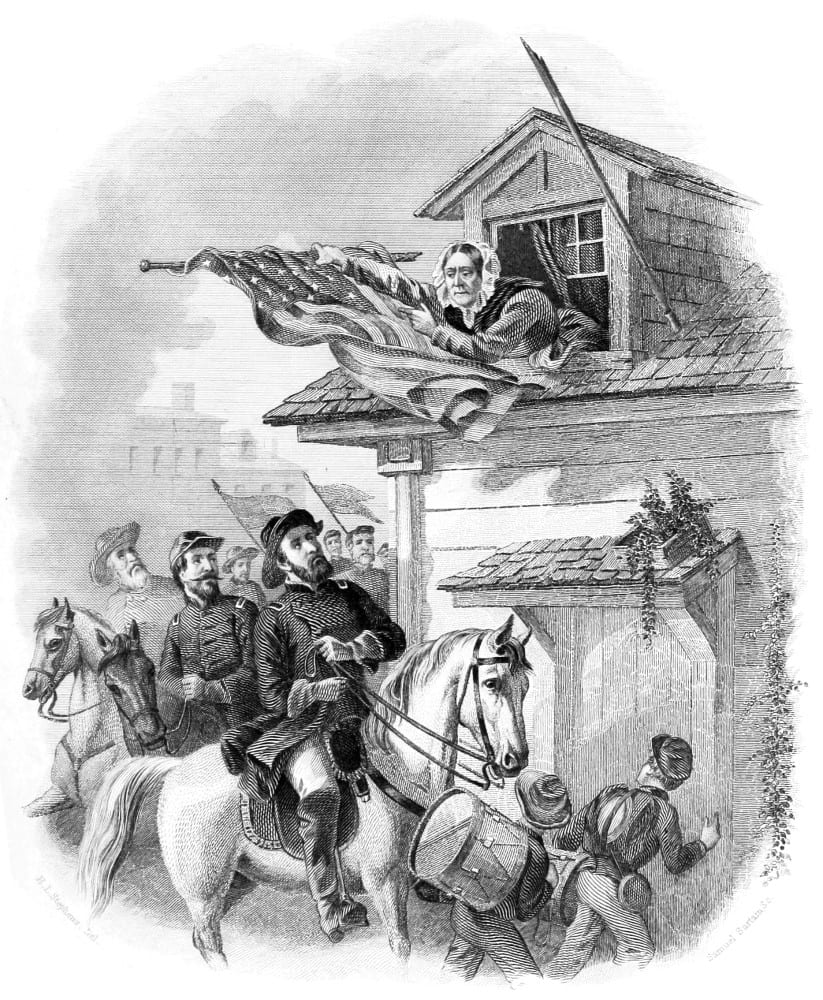

“Barbara Frietchie,” a poem by John Greenleaf Whittier, was published in The Atlantic in 1863 and attributed a defiant act of political rebellion to the nonagenarian resident of Frederick, MD that reduced Confederate General Stonewall Jackson to shame.

As Confederate soldiers advanced on Frederick, the flags that adorned the staunch Union town were removed, ostensibly to protect the village from Confederate attack. Frietchie scoffed at such craven submission:

Up rose old Barbara Frietchie then, Bowed with her fourscore years and ten; Bravest of all in Frederick town, She took up the flag the men hauled down; In her attic window the staff she set, To show that one heart was loyal yet.

- What to watch at Charles Town this weekend

What’s on tap at Charles Town Races? Here are a handful of races and runners we’ll have our eyes on.

What’s on tap at Charles Town Races? Here are a handful of races and runners we’ll have our eyes on.

Spotting the flag as he entered the town, Jackson gave the order to shoot it down, an action Frietchie would not let stand:

Quick, as it fell, from the broken staff Dame Barbara snatched the silken scarf; She leaned far out on the window-sill, And shook it forth with a royal will. “Shoot, if you must, this old gray head, But spare your country’s flag,” she said.

A triumphant tale of resistance against the rebels, the poem may well be rooted in history, but Whittier’s poem has been debunked by historians, who believe that it was not Frietchie but a woman named Mary Quantrell who stood up to the encroaching army.

Nonetheless, it is Frietchie who lives on in lore, both at Laurel Park and in Frederick, where her home has been reconstructed and is open to visitors. That story of patriotic defiance came to mind again in early January when U.S. Capitol police officers tried to fend off a rebellious mob, in the process quite likely preventing the loss of many more than the half-dozen lives the would-be insurrection took.

One might reasonably argue that the Fritchie is the race that should be re-named, to the Mary Quantrell, but this week’s contretemps, justified or not, highlight the re-examination of not only small stories in our country’s history, but big ones, too, especially those that involve the Founding Fathers.

Attempts to re-assess the legacy of George Washington and other leaders of the Revolution are often met with their own kind of resistance, with outrage at the very idea that the man who helped create this country might be subject to historical review.

What Washington accomplished is inarguably admirable; he helped build a new country and political system from the ground up, based on the Enlightenment ideals of freedom and justice.

It’s also true that that freedom initially benefited only those like Washington himself: white men. Neither the Declaration of Independence nor the Constitution offered, much less guaranteed, freedom to women or enslaved people. The writers of the Constitution chose to leave slavery out of the document because they feared that if they advocated for its abolition, the Southern states whose economy relied on the enslavement of millions of people would not ratify it.

- Coal Battle’s West Virginia connection

Kentucky Derby contender Coal Battle has a couple of big fans in West Virginia, whose connection is through the horse’s WV-bred dam.

Kentucky Derby contender Coal Battle has a couple of big fans in West Virginia, whose connection is through the horse’s WV-bred dam.

And the support of slavery was not simply passive. Indeed, Washington, Jefferson, and others were themselves slaveholders, benefiting from the forced labor of enslaved people.

Does any of this mean that the name of the General George Stakes should be changed?

Reasonable minds can disagree, but it’s worth looking at the issue from a broader perspective. There’s no question that Washington made enormous – indeed, incalculable – contributions to the United States.

So, too, have millions of African-Americans over the centuries. But there are no stakes races named for any of the enslaved Black people on whose labor the state of Maryland relied and who to a not insignificant extent built the nation. (Maryland’s lone stake named for a Black person, the Harrison Johnson Memorial, honors a local trainer who perished, at age 45, in a plane crash).

There certainly is no shortage of worthy choices.

The great abolitionist and orator Frederick Douglass was born in Maryland. So was mathematician, astronomer, and abolitionist Benjamin Banneker. The Underground Railroad’s most famous and successful conductor, Harriet Tubman, came from Dorchester County on the Eastern Shore. Samuel Ringgold Ward, who escaped enslavement to become an abolitionist, author and editor also came from the Eastern Shore, while the missionary Amanda Smith, who later opened an orphanage for African-American girls, was born a slave in Baltimore County.

And that’s to say nothing of the contribution of more modern Maryland Blacks, like Dr. Carl Murphy, Billie Holiday, Henrietta Lacks, or Lucille Clifton.

Ultimately, naming a race for George Washington is political. Changing the name of the race, or objecting to changing it, is political. Ignoring the history of Black people in Maryland is political.

But energy spent taking up metaphorical arms to defend or condemn the reputation of a complicated, flawed, esteemed white man would be far more usefully deployed to honor the people our official histories have overlooked and to overhauling the systems that bear the stamp of slavery’s legacy.

LATEST NEWS

Well said, Teresa. Thank you!

I like Wokest as the name for a horse; think about it, all-inclusive !